Us and them

If you're like me — and I suspect many readers are — you've tried to move beyond thinking in terms of ‘us and them.’ It seems, well, divisive. Rather than focusing on differences, I strive to find common ground with others, at least inside my own head. I try to understand opposing viewpoints and how those who hold them have developed their beliefs. I feel this is fundamental to being a healthy and functioning human.

As we often hear in the environmental movement, we all need clean air, water, and food to thrive, so logically we should all be working together to achieve our goals. This statement is simultaneously true and naively simplistic. We should be working together, but we obviously aren't. There are people who have no regard for the natural world and are actively and vigorously working to destroy it. Even among those who identify as environmentalists there can be found fundamentally differing values and objectives. There is also a large percentage of the population that is seemingly oblivious to the situation. In other words, there really is an ‘us’ and a ‘them,’ and it's best to acknowledge this fact from the outset in order to understand how to remedy it.

Working in the landscape industry for the last 10 years I've been exposed firsthand to how average Americans think about the world outside their doors. In a seminar about meeting customers’ needs (aka selling stuff) by better understanding their mindsets, the presenter separated clients into groups. The smallest — a tiny minority — was composed of people who love plants and will arrive at a retail outlet looking for a specific plant they know by name. These folks often do their own designing and landscaping and like to chat about plants and gardening. I easily recall this category because I belong in it. The description fits me exactly.

There were some other slightly larger but not very consequential categories discussed which I don't remember. What stuck with me was the explanation of another group, vastly different from mine, and the largest of all. These folks were described as knowing little about plants, and not very interested in learning. They mainly wanted nice landscaping for the purposes of status and increasing the value of their homes. I immediately recognized this group because it is the bread and butter of the landscaping industry and I interact with these folks all the time.

Imagine foundation plantings of diminutive boxwoods, arborvitae, and false cypress with perhaps a flowering patio tree in the yard, underlaid with a blanket of dyed mulch atop landscape fabric. This is a typical look for this cohort. My point isn't to criticize their esthetic choices, but rather their relationship with their land. Members of this group view the outside of their homes as an extension of the inside, a space to be designed and as one would a living room or den. They value a neat, spare look that is easily maintained with a bit of attention a few times a year. Interactions between wildlife and the landscaping are generally not considered at all, though sometimes they eschew certain flowering plants that might attract bees.

Members of this group might have a great appreciation of nature and enjoy hiking and camping, but carry out these activities elsewhere. The area surrounding the house is not recognized as an ecosystem and there is no concern for wild plants and animals that previously lived there. These are the folks that Doug Tallamy is focusing on with his call to include natives in landscapes and reduce lawn areas. On the whole I would say they are oblivious to the call. They value the exotic look of non-natives, like to fit in rather than stand out, and don't want to be the weirdo on the street with the messy plantings. HMO's play a huge role in preserving the landscape status quo, but even in my town where they are fairly uncommon, the pressure to conform is strong.

It's easy to view this group as ‘them,’ but this huge percentage of homeowners has the potential to make a big contribution to conservation and restoration efforts. Each year as part of my job I speak with thousands of people seeking answers to landscaping-related questions. Anecdotal evidence from these conversations suggests that public information campaigns have an effect. Knowledge of the plight of the monarch butterfly has induced gardeners to seek out milkweed plants, and concern for bees has raised awareness of the dangers of neonicotinoids. There's even some pushback against Roundup, with some customers opting out of use even when it means putting up with weeds.

Consciousness may be rising, but there's a long way to go. Butterfly enthusiasts are planting nectar producers, but without the understanding that specific host plants are necessary to feed caterpillars as well. Bird watchers shop for native berry-producing shrubs, but still spray insecticides which kill off insects that are the mainstay of avian diets. It's encouraging that people are making an effort at conservation, but dismaying that there is such a huge deficit in understanding of the interconnected nature of food webs and habitats.

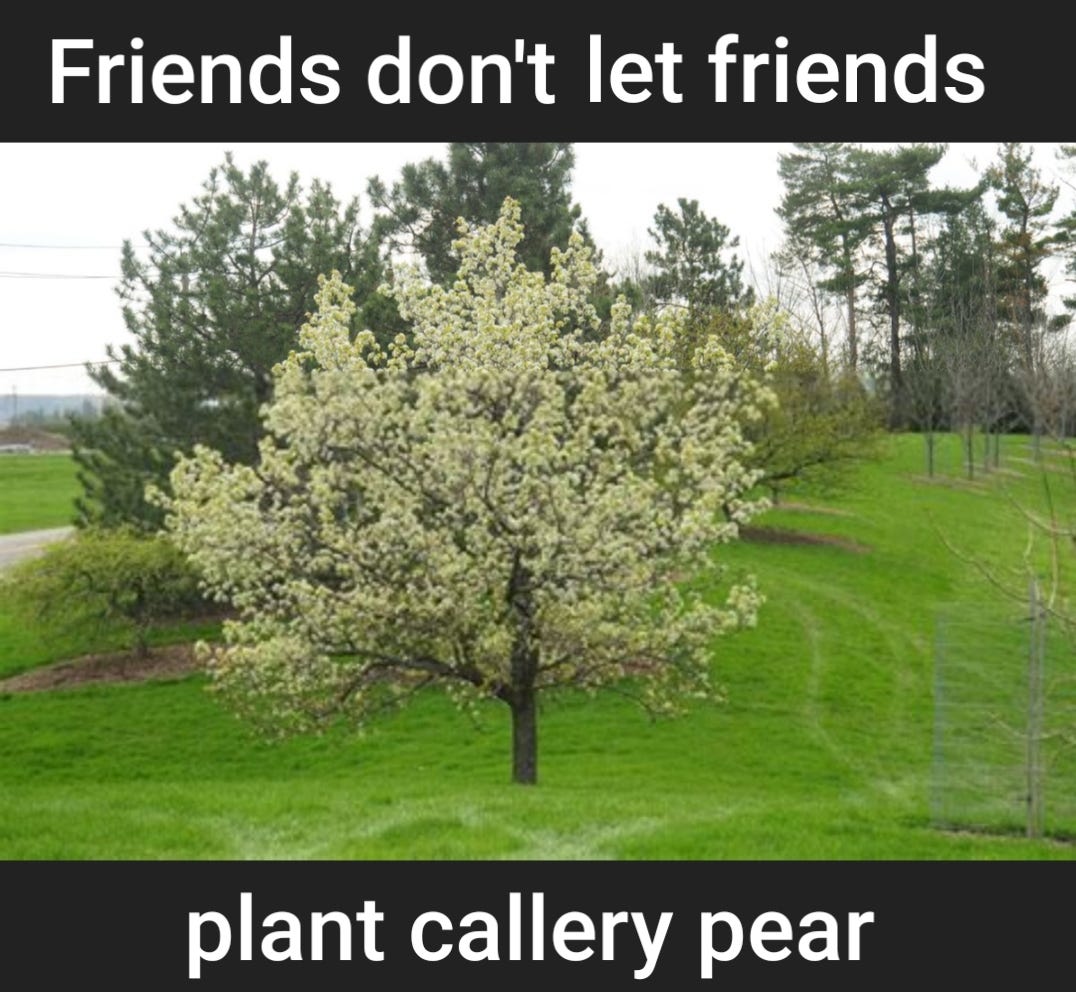

The general public is in sore need of a lesson in ecology. I don't really know the best way to go about this, I just know we have to get beyond linear instructions like “plant milkweed to support monarchs” and “stop using neonics because they kill honeybees.” These recommendations are helpful and effective, but need to be jumping off points for deeper education about the ecosystem in the backyard. The challenge is fitting the message into a Public Servive Announcement one-liner. Or perhaps having so many one-liners that people get the message. I hope you've enjoyed my recycled PSA memes. If you have suggestions for more, or other ideas about how to get the word out, please share in the comment section.

I’m glad you reposted this. I think we all need to know more about the natural world around us. This is part of Indigenous Wisdom, and it has been lost. Have you read Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer? I’m going to keep this in mind and hopefully educate myself more as I step into another gardening season.

I’m speaking at a native plant event on April 15, focusing on the many excellent native edibles to try to get people excited about natives in general but also to go beyond the typical flowers everyone plants.