Notes from the Kanawha Section, Part 1

Thoughts on Appalachianhood and belonging to a place

As much as I've written about the importance of place in gardening and habitat restoration, it may seem surprising that while growing up in southeastern Ohio I was unaware that I lived in Appalachia. My parents had a deep connection to our county that reached back generations, and their identities were closely tied to the hills that jut up north of the Ohio River, but they did not speak of being Appalachian. Nor did my teachers or other adults in my life.

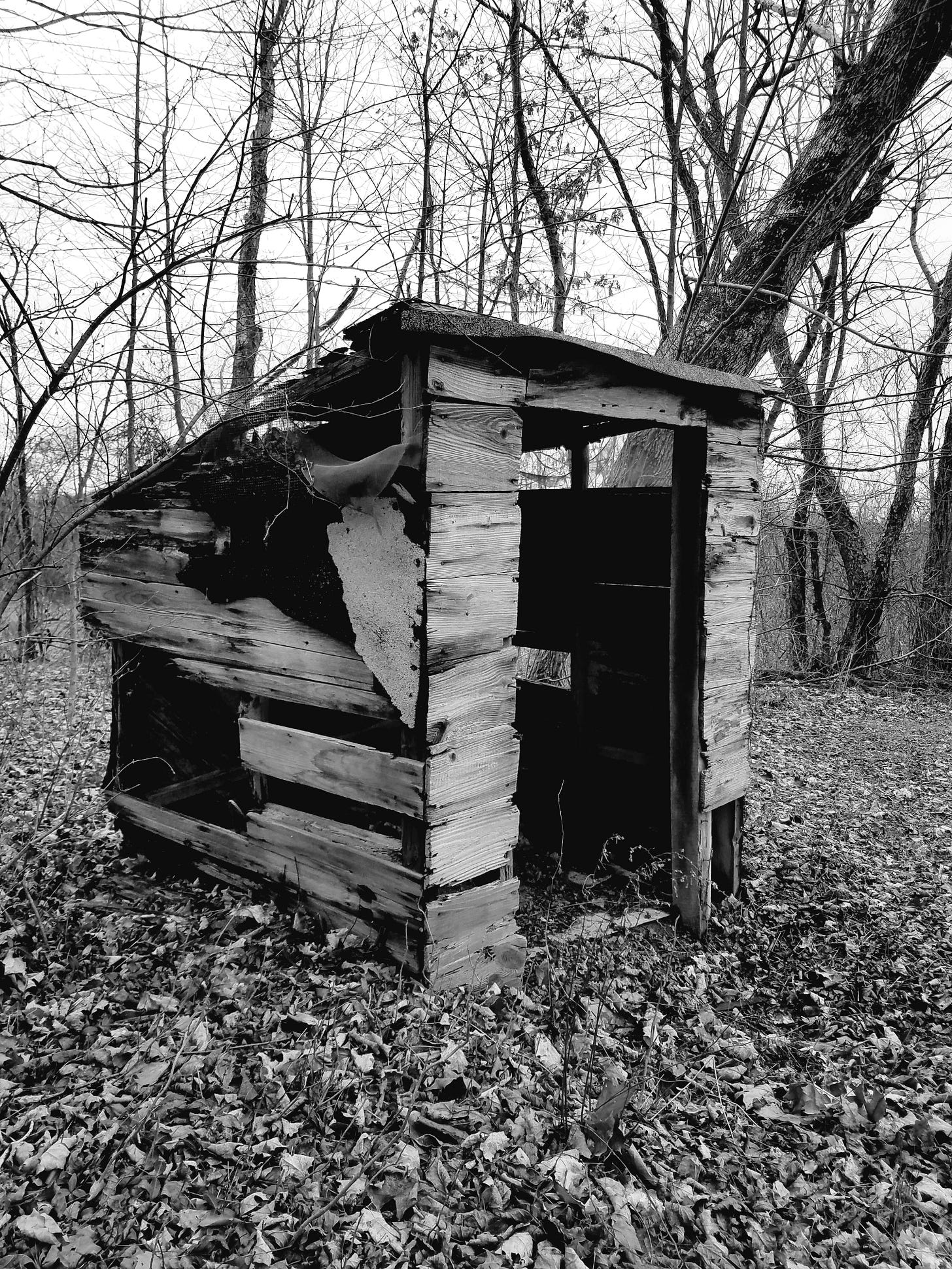

I associated Appalachia with high altitudes, deep hollers, and smudge-faced kids hanging off the porches of tarpaper shacks — places much more wild, remote, and poverty-stricken than the Mid-Ohio Valley. I grew up well to the west of the range known as the Appalachians, and far north of the iconic coves and peaks of the Great Smokies. We definitely had our share of low-income families living in trailers, but I never attached any regional significance to them. Nonetheless, as I discovered in adulthood, this corner of Ohio is considered part of Appalachia.

The United States Geological Survey divides the lower 48 states into eight physiographic divisions, with the Appalachian highlands covering much of the eastern US with the exception of coastal areas and the Deep South. If we went by the map below, a much larger section of the population would be considered Appalachian.

The designation is cultural and socioeconomic rather than purely geologic, and the Appalachian counties are generally considered to reach from eastern Ohio and western Pennsylvania southwest to northern Alabama. The Appalachian Regional Commission, an economic development organization, includes parts of New York and Mississippi. Purists often define the region as only the most mountainous parts of West Virginia, Kentucky, Virginia, the Carolinas, and north Georgia. The category is obviously somewhat open to interpretation. Peripheral counties might petition to be included if it facilitates the flow of federal grant monies, while mountain folk no doubt dispute the inclusion of flatlanders like me.

Defining characteristics of the region are a preponderance of Scotch-Irish and German settlers of a independent and self-reliant nature, relative poverty, historical inaccessibility, and distrust of authority and outsiders. My ancestors were of the correct genetic stock and socioeconomic status for qualifying as Appalachian. They were notorious jerryriggers and occasional moonshiners. They were gardeners, quilters, and milchcow keepers who repurposed flour sacks and saved small bits of string. They also apparently eschewed travel, a characteristic that purportedly gave rise to communities cut off from their neighbors.

The fact of travel being more difficult within the Appalachian region, as opposed to the coastal and piedmont areas to the east, and the plains to the west, is the ostensible reason for the relative poverty and the Galapagos-like development of isolated and distrustful communities. In fact, terrain is often mentioned as the major factor in the development of a specifically Appalachian culture.

The concept of inaccessible land is somewhat incomprehensible in our era of almost ubiquitous car ownership, considering that even with stretched local and state budgets, relatively good roads reach nearly every inhabited house. But in the not so distant past, the rugged terrain of Appalachia presented an obstacle not only to westward migration of Europeans, but to those already settled here.

An oft-repeated saying in my family was that our ancestors crawled down out of the hills to discover that “the rest of the world talked funny.” To put this in perspective, it's necessary to point out that we were speaking about a movement of less than 30 miles laterally and only about 500 feet vertically. I'm certain there is a dose of hyperbole here, but the contrast between my hill farmer forebears and the folk of the bottomlands was significant enough to be remarked upon many years later.

Whether they rarely made the trip due to its difficult and time-consuming nature, or because they simply had no reason to, is unclear. I question as well whether they were distrustful of outsiders. Is this really a regional trait, or are stories such as the saga of the Hatfields and McCoys simply more entertaining than a narrative about humble folks keeping to themselves and taking care of their neighbors? The predominant attitude I've gleaned from family stories is much closer to “live and let live,” than “grab the shotgun, there's a stranger on the road.”

I'm not terribly concerned with proving my Appalachian-ness. I spent most of my life not being from Appalachia and I was fine. It would be nice, though, to fit in somewhere and cease to be mistaken for a Midwesterner. But debating the authenticity of those living within the nebulous boundaries of the area known as Appalachia seems to me a pointless excercise. In a region supposedly full of self-reliant individualists, fiercely loyal to kin, but suspicious of folks the next town over, there is irony in the idea of a regional identity.

When I was a student in Asheville, North Carolina, it wouldn't have entered my mind to claim to be from Appalachia. If I had done so, my fellow students who were born and raised in the southern highlands would have reacted with laughter and scorn and viewed me as a poseur from the urban North. Their concept of Appalachianhood extended only to those with personal experience from birth of the rhododendron covered slopes of their state and select counties of neighboring Tennessee, Georgia, and South Carolina. This pride of place and heritage is commendable, and we need more if it, but without the self-conscious obsession with authenticity.

During my college stint in North Carolina, among the out-of-state students was one from New Jersey whom I will call Bob. Unsurprisingly, given the reputation of his state, Bob was constantly in the position of defending his home, and he never gave an inch. Attempts to bring up the alleged wretchedness of Jersey would cause him to launch into glowing descriptions of the Pine Barrens, an area he was intimately familiar with and obviously loved. He deplored stereotyping, and wasn't going to give in to an outsider’s view of his beloved state.

The moral of the Bob story? There are several possibilities. “Stop stereotyping, because you don't really know a place unless you're from there.” “There is beauty left in the most unlikely places if only we care to look.” “Don't argue with someone from New Joisey.”

How about this one: In the same way that environmental conservation isn't just about saving charismatic megafauna, but also protecting lowly and hidden creatures like nematodes and moles, love of place isn't only about cherishing and protecting majestic peaks and pristine beaches. It's about learning to love the place you're in enough to work to protect and restore it. My takeaway from Bob: My little corner of the world is special and unique whether one thinks of it as authentically Appalachian or just backwoods Ohio.

The concept of Appalachia as a place to be from is intriguing enough for me to dedicate this piece of prose to exploring it, but at the end of my inquiry I arrive at the fact that, in part, Appalachia has degenerated into a brand. Like “Amish Country,” it is now something to be capitalized upon. Local shops and festivals advertise themselves as Appalachian. A non-profit association, Ohio's Appalachian Country Inc., exists to promote tourism in eastern and southern Ohio. I suspect that elsewhere this happened a long time ago and we're just now catching up.

There's nothing inherently wrong with this development. It's not like anyone is lying. This is a beautiful place with a rich history and lots to see and do. I support tourism as a path to sustainable livelihoods, and as an alternative to the ghastly industries of extraction and processing that are important employers currently. Besides, it's 2024 and we should all be used to watching everything eventually devolve into commodities, right?

Maybe divorcing ourselves from any concept of regional identity, and simply focusing on being like Bob is best: Learn to know and love a place as deeply as you can whether you're from there or merely landed there by chance, and don't let anyone get away with telling you it isn't worth loving.

Thanks for reading!

Being from Central Ohio and living in the county where Malabar Farm resides I have always been puzzled by the bad rap Ohio gets. I think it’s a beautiful state if only one takes the time to look. Thanks for this piece!

Here is an outsider's view of Ohio:

I became interested in Ohio after I discovered the agricultural writings of Louis Bromfield. It took me another nine years to make a road trip to Malabar Farm State Park, the former farm of Bromfield, that he restored to productivity from ruined soil due to poor farming practices. I was blown away by the beauty of rural Ohio in June. I was particularly taken by southeastern Ohio. I did not go to any of the really big cities, the largest I passed through was Marion.

In my opinion, American children's literature reached its zenith in the 1950's and 1960's. Since it almost exclusively came from the east coast, there was a flavor about the books, particularly the illustrations, that had a "somewhere else" feel to a western kid like myself, who loved to read. I remember the shock I felt as a child finding a series of books about my own area. In my child's mind, somewhere there was an Americana-style small town, with cardinals and blue jays... I just didn't know where. In 1997, to my surprise I found that place in every small town I passed through in Ohio. I loved Ohio in June, but I'd probably hate it in winter ( I dislike cold and snow). I chanced on your Substack, and was interested when I realized you were writing from Ohio. BTW, my two deleted comments are because Substack has a nasty habit of deleting my comments if I make one wrong move. I don't have a desktop or laptop.