Errors of logic, and beyond

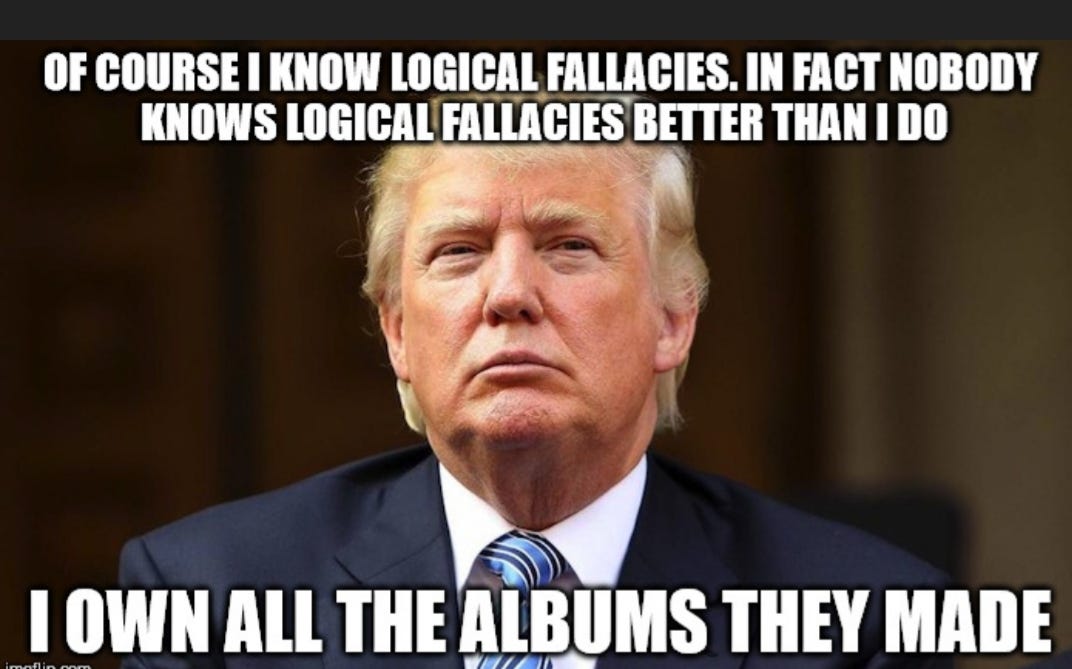

With memes!

A few years ago I had a conversation with an acquaintance about her currently being a vegetarian, and working toward a vegan diet. The reasons she gave were that, in general, foregoing meat, dairy, and eggs is probably a) healthier, b) kinder to animals, c) reduces deforestation especially in the Amazon, and d) produces less greenhouse gas emissions. While compelling arguments might be put forth for all of these things, she didn't admit to being more influenced by one over the others. It was more a case of four probables adding up to one definite. If each justification for going vegan was weighted at 25%, then four reasons added up to 100%.

I didn't argue with her. I was pretty sure that the morality of confining and killing animals was her main impetus for avoiding meat, and I respected this. Ethical beliefs aren't open to the same arguments as ones involving nutrition or emissions, in which scientific evidence might be introduced by both sides. I felt that in her real reason for yearning toward veganism, there was no error in logic, but rather a true caring, the wish never to be the cause of an animal's suffering, the desire to be a good person.

On the other hand, I felt she was committing a grave error of logic in her stated reasons for adopting a certain diet, and had fallen into a trap often set by skilled propagandists. The collective mass of a dozen weak reasons why x might be true, doesn't add up a strong case for x being true. In fact, such reasons cannot be added up at all, and the merits of each argument must be examined and judged separately.

A version of this tactic is a well-worn tool of conspiracy theory peddlers: relying on quantity of information to make an argument rather than quality. They exploit the fact that most people naturally seek out as much information as possible from various sources in order to make decisions. The illusion of truth can be created by bombardment with facts, interviews with experts, and a plethora of peripheral information, even when each individual component doesn't stand up to scrutiny, or isn't terribly pertinent.

My vegetarian friend, already leaning toward a vegan diet, used a constellation of related arguments to bolster her beliefs without necessarily investigating their robustness. Am I seeking to invalidate her decision to go vegan based on the possibility that one or more her justifications lacked merit. Nope. To do so would be to commit a further error of logic. One good, solid reason is enough, and though I don't share her commitment to never eating animal products for ethical reasons, I respect it.

My friend's dietary decisions are no doubt right for her, and ultimately none of my business. And if I notice errors in logic, I usually keep it to myself in order not to be viewed as an insufferable pedant. But sometimes I privately make this face when I read or hear certain things:

For example, did you know that purchasing less beef in the U.S. will result in a consequent reduction in Amazon deforestation? My vegetarian friend was of this belief, but it was already proven wrong before it became popular. The reasoning goes that in a country where demand for beef drops, producers will then export their beef, lessening pressure for production elsewhere.

According to the CLEAR (Clarity and Leadership for Environmental Awareness and Research) Center at UC Davis, beef consumption in the U.S. has been dropping for decades while exports have been rising, but Amazon deforestation has increased during the same period. This is explained by the fact that beef produced in the U.S. is of different quality and bound for other markets from that produced in Brazil. American beef tends to be grain-fed, marbled with fat, and sold for top dollar in high-income countries. Brazilian beef is in general grass-fed and leaner, and exported to different markets in poorer countries. Land clearing for beef production in Brazil is driven by rapid growth of markets in lower income nations.

These facts are available to anyone curious about the effect of their supermarket choices on Amazon deforestation, and are real-world evidence that, at least where beef is concerned, your grocery purchases in the U.S. have no effect on rainforest deforestation. Even though global markets are interconnected these days, it doesn't mean our consumer choices can influence them in the ways we wish. For a boycott such as this to work, it would need to involve a very large, focused group of consumers whose purchases or lack there of were directly linked to markets and producers.

Belief that buying something other than beef in the U.S. will have repercussions in Brazil just doesn't pan out, but there's a deeper illogic to this line of thinking that must be considered. Even if there was a correlation between purchases here and production in South America, it's not as simple as just not buying beef: Every steak not purchased must be replaced with comparable calories and nutrition, and growing food takes land. There are only a few ways to increase available food: existing farmland must produce more, abandoned farmland must be restored and utilized, food waste must be curtailed, or crops must be grown in new areas. Whether you eat brisket or beet greens, pot roast or potatoes, it must be produced somewhere. If demand for grains and vegetables increases, producers will grow more. Wherever potential profit, land access, climate, and local laws are amenable, land will be used. If you wish that rainforest — or any other intact and functioning ecosystem — not be bulldozed, burned, or otherwise destroyed for new farms, you'd better get to work on the other three options.

Another error of reasoning crops up in discussions of invasive species. In this long-running debate, stances range from advocating for total eradication of non-natives to doing nothing at all, with many perspectives in between. There are two main camps, however, one believing that certain plants and animals arriving from elsewhere can pose a threat to local ecosystems, and those who view the concept of invasive species as flawed, and see no reason to control the spread of any species.

Some critics of the concept of invasives attempt to invalidate it by pointing to the fact that those who accept it often use herbicides in the quest to eradicate invasive plants. But the fact that some people make the decision to use poison to control unwanted plants is not a consequence of belief in invasive species. One can believe in the concept of “invasive” or not, and one can use herbicides or not, there is no cause and effect relationship here.

This tactic is a version of the guilt by association fallacy: A belief is tainted because bad actors (herbicide users) also hold the belief. Another example is when critics point out that some people who believe in invasive plants also hold offensive racist, colonial, or religious beliefs concerning purity.

Using such associations to discredit the idea of invasives avoids the core concern: Certain species are either doing damage to local habitats or they aren't. Obfuscating the issue is the fact that few people know enough about the natural environment outside their doors to make a judgement on whether harm is being done or not. This is really the crux of the matter — without the knowledge to decide whether an exotic species is doing damage, we're left floundering and dependent on the sorts of peripheral concerns outlined above to make up our minds.

The real solution here isn't to examine various perspectives in order to identify logical errors (although this is important!) To make any kind of meaningful evaluations we need learn much more about the organisms with which we share habitat. Without such knowledge there is no way to even define what “damage” means, and the concept of invasive species is as nebulous as critics claim it to be.

While I'm always on the lookout for things that make no sense logically, I'm also the first to admit that logic isn't everything. I can state, for example, that the central question is whether exotic species are doing damage or not, but what constitutes damage and whether we should worry about it are open to debate. Identifying flawed logic and sweeping it out of the way is important because it allows us to get down to the nitty gritty of the issue and engage in more meaningful discussion.

Identifying distractions is as important as detecting flaws in logic. Have you ever felt that baby boomers are to blame for all of our problems? The thought of blaming an entire generation for society's ills had never occurred to me until five or so years ago when the idea started to appear everywhere, probably as a result of Bruce Cannon Gibney’s book, A Generation of Sociopaths. I haven't read the book, but judging from reviews it seems to be a serious attempt to catalog the bad things that happened as boomers came of age and dominated politics and culture.

I would like to state clearly that I agree that many horrible decisions were made during this time, as is true for every era in American history. Good history books, however, examine historical forces in effect prior to and during a particular time period, and explore the influence of powerful individuals and institutions of that time. Were the boomers among the 29 million people (Census data) living below the poverty line in 1980 as much to blame as the boomers who were wealthy? Of course not, and it makes sense to hold people responsible relative to the power they hold.

I think everyone intuitively understands this, but it just feels so good to have someone to blame, especially if it happens to be an older generation who has been blaming your generation for everything, and you're looking for some revenge. It makes for great memes, but unfortunately it's a distracting stand-in for meaningful analysis of power and class. It's easier to scroll through boomer- (or millennial-) bashing memes for that addictive combination of simplification, humor and confirmation of existing beliefs, rather than to think.

There's an epidemic of this kind of distraction. Look at the Springfield, OH, situation. So many issues and all most people know is that imported workers might be eating pets. Logic, or flaws thereof, need not enter the picture if observers are distracted by the ridiculous and the peripheral.

What's really going on in Springfield, Ohio? What does effective activism to stop rainforest deforestation look like? Is the housing crisis really the fault of stubborn oldsters? What are the causes of ecosystem degradation and should you worry about exotic plants? Opinions will differ on each of these topics, but getting past distractions and flawed logic will leave us better equipped to form those opinions and engage in meaningful dialogue.

Your reasoning is sound I admit but I think it's hard to be up to date on every issue and sometimes I just have to decide what feels right. Should I buy this fruit that's out of season in my hemisphere? I pick no. Should I take a drug to make me thin? I pick no. Should I kill the spider in my bathroom or gently move him to the window. I pick window. Should I go by bike or car? I try to go by bike whenever possible. I mean, I have no idea if it's somehow beneficial to the general well being not to kill the spider in my bathroom but it feels right. Will all those ugly memes adversely impact the lovely photographic ambience of Turtle Paradise? I pick Paradise. That said, you make many valid points about bigger issues than the ones I mentioned above. I would very much like to become a vegetarian but my wife is a total carnivore. Life is complicated.

I'm sorry you felt the need to use the CIA-created term "conspiracy theory"...but that is not my primary comment. Before I make my point...a story.

When I was a child we had two beeves we raised together, a red steer and a black steer. The local butcher drove around in a white van. He shot the animal on site, and cut it up, and then went back to his tiny shop (where a relative of mine worked as butcher's assistant) to process the meat. We always spent the day away on butchering day. The black steer went first. Two years later, we returned home on butchering day to find the red steer very much alive. With a call to the butcher, we learned what happened. When the red steer saw the white van, he went berserk. Imagine, seeing you best friend shot, and butchered before your eyes. That steer probably was waiting for his turn to come. This old-time butcher would NEVER shoot an animal if it knew it was going to die. He said it ruined the meat from the adrenaline and other chemicals a frantic animal produces. He had to come back another day in his car to shoot the steer, and then quickly come back in the white van.

I am a vegetarian. I have PTSD. It is crazy for anyone with PTSD to eat any meat filled with terror hormones...which pretty much is ALL meat except animals killed by ambush. I first became vegetarian in 1986 for ethical reasons. In 1999 I almost died from a yellow fever vaccine. I contracted yellow fever from the live virus in the vaccine. I then was at death's door from 2000 to 2004. I NEVER saw any practitioner. I CURED myself. One thing I did was become vegan overnight. It was one of the most difficult things I ever did...but it saved my life. I was following the the Dr. Lorraine Day holistic cure plan. After I recovered, I went back to being a vegetarian. I was left with MCAS, and drinking a gallon of goat milk a week is a major part of my healing diet. I believe being a vegan for a limited time is nessecery if one's body is highly toxic, as my body was. To stay on it full time, one would have to work extremely hard to get all the nutrients they require. However, an unhealthy vegan diet would still beat the average American diet, as far as health goes.