Are hurricanes getting worse?

The soft side of Helene, attribution science, and what we mean when we ask if storms are worsening

Helene brought clouds and cool, misty rain to the Mid-Ohio Valley, weakening the grip of the drought and heat that have plagued the region for months. While the hurricane delivered devastation farther south, here it arrived gently, with spectacular skies and a pleasant drop in temperature. Plants responded by perking up or — in the case of those nearing the end of their life cycle — erupting in fungal growth.

While Helene is cursed in the southern Appalachians, the fact remains that hurricanes serve a purpose: They regulate global temperatures. They are the inevitable result of equatorial regions receiving more direct solar radiation than other parts of the globe. Along with ocean currents, atmosperic events such as hurricanes and typhoons move hot air from the tropics toward the cooler poles, maintaining balance. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, such storms “take heat stored in the ocean and transfer it to the upper atmosphere, where the upper level winds carry that heat to the poles.”

Hurricanes often coincide with late summer dry spells, and bring welcome rain to drought-stricken regions. They fill rivers and streams and replenish aquifers. They destroy, but they also build by raising sand and depositing it elsewhere, sometimes creating new barrier islands in the process. These intense storms participate in the fertility cycle by churning up nutrients offshore and moving them far inland, and carrying seeds far beyond their usual range.

If we exclude human concerns, hurricanes are less agents of destruction, and more events that just mix stuff up. Plants and animals die, but in the long term, there are positives: Fresh water, heat energy, and fertility are moved from areas of high concentration to areas where life can put them to use. When a hurricane with its entourage of tornadoes scours stream beds and flattens forests, a patchwork of habitat emerges, often with greater species richness. Though the initial damage is extreme, in healthy ecosystems plants quickly take over and heal the wounds.

Of course, we can’t exclude human concerns, and from a human perspective hurricane revovery is quite different. The effects of loss of life reverberate for generations. Rebuilding the damaged infrastructure of our industrial culture requires enormous labor and resources and in some cases isn't possible. The damage incurred often extends beyond the locality impacted. Since we humans have a habit of concentrating toxins, chemical storage facilities, refineries, manure lagoons, and the like that are damaged in storms send their poisons far downwind and downstream.

Helene was particularly horrific in its destruction, and in the aftermath came the flurry of headlines insisting that climate change made the hurricane worse. This makes logical sense: Warmer ocean waters mean more energy for storms to draw on, and greater heat that must be moved toward the poles. Warmer air holds more moisture so more precipitation can be delivered. How much worse was the storm than it would have without increased atmospheric CO2? A new field of study called attribution science has sprung up to answer this question.

One organization tackling the problem is World Weather Attribution, a coalition of researchers formed in 2015 with the purpose of conducting rapid attribution studies on extreme events. WWA works to answer three questions:

How did climate change influence the intensity of the event?

How did climate change influence the likelihood of the event occurring?

How did pre-existing vulnerability worsen the impacts of the event?

Within a few weeks of Helene’s landfall, WWA issued a report. Among other findings, researchers found rainfall to be 10% heavier than it would have been in a non-warming world, and that storms such as Helene are now expected once in 53 years, rather than once in 130 years as in the past. They also identified major factors that exacerbated the effects of the storm: a previous extreme rain event that left soils saturated, the steepness of the terrain in much of the effected area, and less hurricane preparedness so far inland.

It's not unreasonable that there could be rigorous science to back up these findings, and those literate in the scientific method with access to research papers and time to read them can judge for themselves. The vast majority of the public however, myself included, rely on easy-to-read articles to gather information. Such content not only doesn't explore research methods, it rarely explains what is meant by claims that weather event are becoming “worse.” It has become one of those things that is understood to be so obvious and self-explanatory that no clarification is needed. This is intellectual laziness that reduces the value of any writing on the topic. While the jury is out on the value of WWA research, their breakdown of the topic into the three questions listed above is useful because it helps us understand what “worse” can mean: greater intensity, higher likelihood of occurrence, and extent of damage and contributing factors thereof.

If we are completely honest, we must admit that we are totally dependent on researchers, working in good faith and outside the constraints of politics, to know if weather events are truly worsening. Science, especially climate research, is almost certainly not free from political pressure. What are the internal conditions inside an organization like the WWA? How policized are they? What influence do financial donors have? Do we have assurance that the core principles of science are being observed? I have no way of knowing and neither do you, unless you have some connection to the field that most laypeople lack. This is not a claim that WWA is corrupt or lacks integrity; it is a declaration of agnosticism in the face of the increasing manipulation and politicization of science and its reporting. It is a commitment to approach what I read with objectivity and skepticism, core tenets of science itself.

Each question investigated by the WWA calls for a different approach. Current weather data is compared to that collected prior to the late 19th century to determine the probability of extreme events occurring before and after fossil fuel burning became widespread. Computer models are run that simulate real world conditions versus a theoretical world in which GHG levels are not elevated, to deem if climate change affected the intensity of the event. (It is crucial to note that carbon reductionism is built in to such models.)

The third question relates to the damage caused by a storm or other event, and it is important to understand that there is not a direct correlation between storm intensity and likelihood, and damage. A monster storm, hyped up on superheated ocean waters, could spend itself at sea and cause little damage. A minor storm could wreak havoc by hitting a vulnerable area. The major factor at work is luck, with human decisions on what to build and where playing a huge role. The third question (How did pre-existing vulnerability worsen impact?) is investigated by counting the dead and tallying up the cost of destroyed infrastructure, and looking at pre-existing conditions that exacerbated effects.

While research in the areas of intensity and likelihood of weather events has value, it is unlikely to have real world implications for a simple reason: Despite global hysteria over elevated GHGs, almost nothing is being done to reduce emissions. Our economic system prevents action. Furthermore, carbon reductionism is built into most research. The burning of fossil fuels contributing to the build up of GHGs is the main dependent factor, with biosphere destruction usually ignored. The most likely scenario for the future is business as usual until breakdown of natural systems brings societal collapse. In my opinion, the real importance of attribution research lies in vulnerability studies, which has little to do with atmospheric CO2.

Let’s return to the question we are all asking after a storm such as Helene: Are hurricanes becoming worse? While headlines scream that they definitely are, likelihood, intensity, death, and destruction are blended together in the word “worse.” We instinctively agree that yes, of course, they are getting worse, but mainly because we are seeing massive destruction on our screens. Bad storms are the perfect opportunity to promote fear, carbon reductionism, and the general sense that there is a simple and direct link between burning fossil fuels and massive, destructive hurricanes.

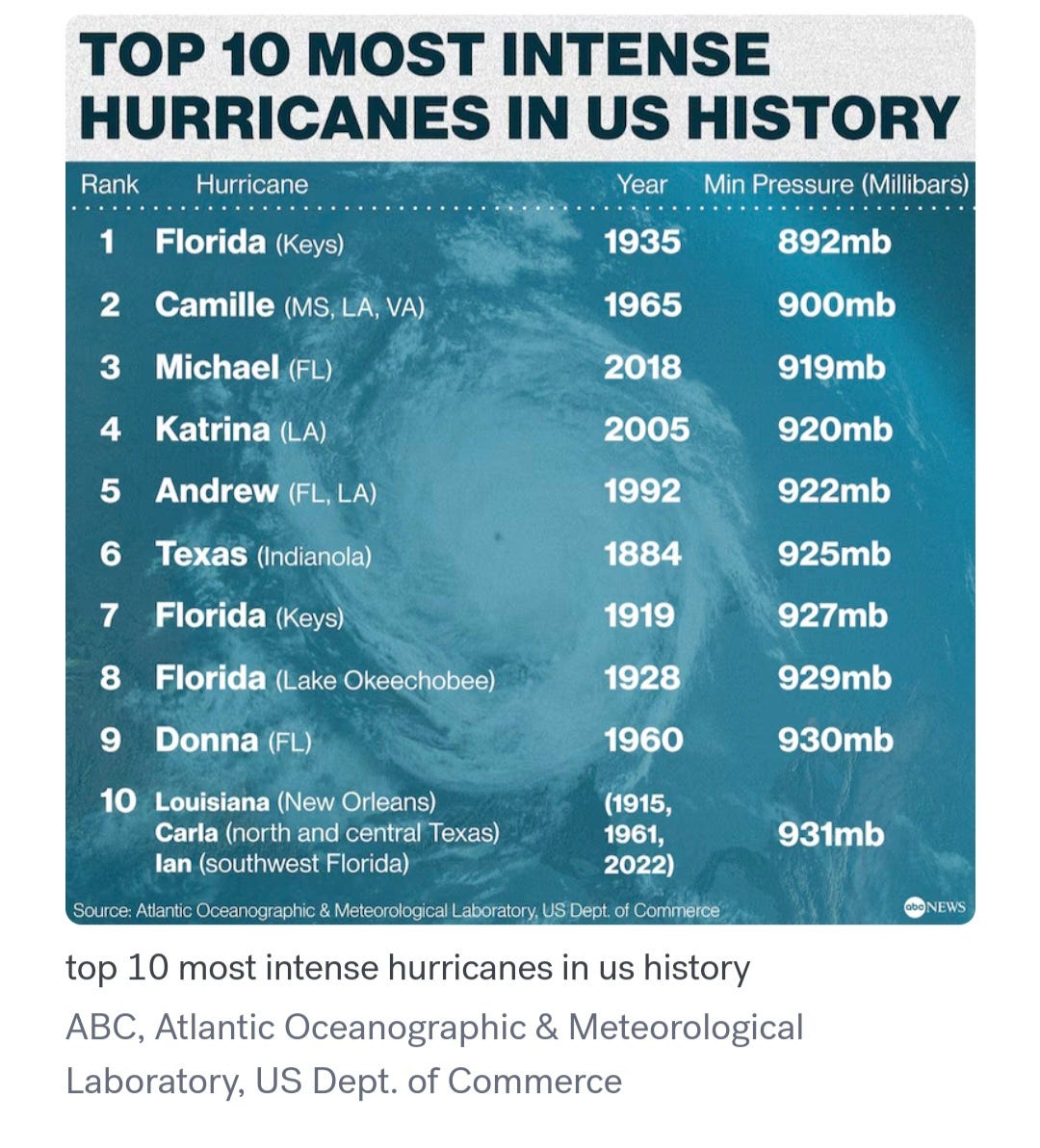

Because I was bothered by the conflation of storm severity and likelihood with levels of destruction, I decided to take a look at historical storms to get an idea of how intensity related to human deaths and property damage. Lists of the worst Atlantic hurricanes to make landfall in the US are readily available online, and I looked for the most intense (measured by internal barometric pressure, a metric that correlates closely with wind speed), deadliest, and costliest.

(Information below comes from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data, with graphics of the first two provided by ABC News.)

(Please note: The Galveston, TX, storm occurred in 1900 not 1990.)

The most notable aspect of the three charts is that only one event appears on all lists: Katrina, the megastorm of 2005 that devastated New Orleans. Not only did it make the cut for each list, it consistently shows up in the top four. But Katrina is a bit of an outlier: Only four additional storms show up on more than one list, and there is little correlation among the three criteria. Many of the hurricanes are unnamed and are identified by the state where they made landfall and the year they occurred. This indicates that they occurred before 1953, the year the National Weather Service began its practice of assigning hurricanes women’s names.

The second notable thing about the lists is the mismatch between deadliest and costliest. With the exception of Katrina, the deadliest storms all hit before 1960, while minus Andrew, the costliest hurricanes all occurred this century. With the exception of Katrina, there is no overlap whatsoever between the costliest and the deadliest lists, though common sense tells us there should be. This situation can easily be explained by two things: technology and stuff.

In the 1800's and into the first half of the 20th century there existed less sophisticated forecasting ability, communications technology, and transportation infrastructure. People simply didn't have as much warning that a hurricane was on the way. Announcements of a dangerous storm disseminated more slowly through the population, and evacuation channels were also slower. It makes total sense that in general, given our current technology and infrastructure, fewer people die in storms.

The enormous cost in dollar amount of more recent events also makes complete sense since there is so much more stuff to be destroyed. Land that was forest and farms mid-century is now chock full of homes, gas stations, self-storage units, car lots, and dollar stores. Not only has our population expanded, our need for stuff has exploded. The 1900 Galveston event — not only the worst hurricane in terms of loss of life but also the deadliest weather-related event in U.S. history — does not show up on the costliest list. In fact, I’ve shown only the top ten of a list of 55 on which Galveston is not present. Though there was staggering loss of life and the storm hit a major port, there just wasn't as much stuff to destroy in 1900.

In our minds, the horrific photos and videos of debris flows, collapsed roads, and destroyed buildings in post-Helene North Carolina bolster the belief that hurricanes are getting more costly, a view backed up by NOAA data. However, the skyrocketing price tag for hurricane recovery has little to do with GHGs, and everything to do with our industrial lifestyles. Similarly, loss of life isn’t necessarily tied to wind speed and internal pressure. All but one on our list of deadly of hurricanes hit before 1960. The big exception, Katrina of 2005, killed so many because levees weren't maintained, and mobilization of rescue resources was delayed and pathetically lacking. People died less because of storm intensity and more because they were simply seen as expendable.

A form of shifting baseline syndrome is at work when we instinctively agree with media assurances that hurricanes are getting worse, especially in term of fatalities. If we lack historical knowledge and personal experience of similar natural disasters, a death count of hundreds seems appallingly high. I think few of us can grasp the horror that our ancestors experienced during the hurricane season of 1893 in which thousands were killed in the Sea Islands Hurricane that struck Georgia and South Carolina in August, followed by the Cheniere Caminada Hurricane in September that hit Louisiana. Each storm wiped out entire communities, and possibly the only reason they don’t rank above Katrina on the deadliest list is because the exact number of fatalities is unknown. Even harder to imagine is the Great Galveston Hurricane of 1900, which might have killed up to 12,000 people.

So are hurricanes getting worse? I would say yes, no, and maybe, depending on what is meant by the question. There is compelling evidence that storms are becoming more costly, but less deadly, for reasons I hope I have explained. If we’re asking if storms are stronger, the answer is maybe. Even if we pare down the question to an analysis of intensity, there are still numerous factors to be considered: rate of development of a storm, wind speed, height of storm surge, precipitation delivered and over how large a geographical area, and number and severity of tornadoes spawned, among others.

Which factor is indicated when headlines inform us that hurricanes are worsening? In quality reporting, a close reading will tell. In most media content, you will more likely find a jumble of meaning with intensity, death toll, and destruction of property all tied up in one package designed to create an emotional response, mainly fear. Fear is not a useful emotion unless it provides impetus for action, and for action to be effective, we need to understand what's actually going on. As we move through the final month of hurricane season, read critically, try to get information from various sources, and keep your bullshut detector turned up to 11.

I really like the way you highlight the different possible meanings of "worsening."

And the photos are juuuuuuust gorgeous! Extra !!! Our state really is beautiful!

It is really tough for us laypersons to tangle with experts on subjects like the science of climate change and extreme weather. I have learned the hard way that's easy to screw up when I leap to conclusions on technical subjects I know nothing about. Like automatically assuming every age related blemish on my skin is probably the cancer that's going to kill me...

On the other hand, I think one thing us non-experts are well-qualified to do, by virtue of being human, is to exercise sound judgment about the motivation and character of experts we deal with, like our doctor, car mechanic, or climate advisor. We all might be asked to make such judgment calls on jury duty at any time.

In that spirit, I'm satisfied that WWA is an activist organization working to maximize public anxiety for political purposes. That doesn't change the very real and scary fact that humans are causing climate change. But WWA is intentionally exaggerating certainty about hurricane severity to create a climate of fear. In their view, this is a justified response to fossil fuel company disinformation. See https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/did-exxon-make-it-rain-today; https://rogerpielkejr.substack.com/p/weather-attribution-alchemy.

Also, I hope society doesn't collapse. My niece will be 83 in the year 2100 and I'm hoping she'll be around for something not resembling a Mad Max movie...

Very informative and well-researched article about a subject I've wondered about. I wish this exact piece could appear in the NY Times or some other national megaphone. Keep up the good work.